There are many ways that a physicist can ‘reach out’ and share their, hopefully infectious, love of science. In doing outreach, I often meet people that have already caught it. I have run stalls at science fairs where I have been bowled over by the knowledge and enthusiasm of young visitors who are able to offer mindboggling facts about the galaxy we live in and the latest discovery, fresh out of the CERN press office. I have presented interactive family shows with exploding hydrogen balloons and levitating superconductors in which eager volunteers excitedly join in with the demos, often with hilarious results. It is a joy to be part of.

But I have found that nothing compares to the challenge and the rewards of going into a school. By taking science into the classroom, you ensure that you not only reach those that are already engaged, but you also meet those that perceive science as nerdy and boring or have prematurely decided it is not for them: those that have never thought of watching popular science programs because the draw of their favourite TV shows and social media are too great. In just one hour, you can see chins-in-hands become raised eyebrows, dropped jaws and gasps of incredulity. That is the holy grail of outreach.

The CDT recently ran a training session for those interested in taking outreach into a classroom setting. We had the opportunity to meet with teachers and find out how they plan and manage their lessons, which usually starts with writing down a set of learning outcomes. I thought about how I could apply this to outreach. It is an interesting dynamic taking outreach into schools: the classroom environment is usually where children must learn specific curricula to pass important exams. On the contrary, the focus of outreach is to excite, inspire and challenge predefined ideas and stereotypes. Learning is of course a by-product, but to my mind it is not the primary objective. My ‘learning outcomes’ were therefore much less topic based and more about the effect I hoped to have. How did I want the students to feel during and after the session? Which ideas did I want to stand out the most? And what did I want the students to go home telling their friends and family about what they had done at school that day?

During the training, we also talked about making the session relevant to the students’ lives. One of my favourite ways to do this is to show them something extraordinary and then demonstrate that the same physics is relevant in something wholly familiar: something that they rely on every day but have never asked the question, how does this work? With the prevalence of novel electronic devices in children’s lives, there is a plethora of such opportunities in physics outreach.

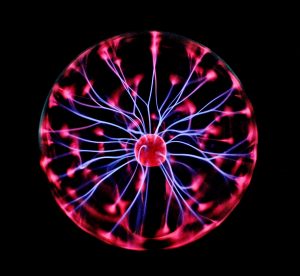

It was not long before we had the chance to team up and put our ideas into action. The outreach I had done to date had all been as an individual or as a pair. Here, we were in a team of 4 and so we decided to make the most of the extra pairs of hands and move away from the ‘teacher at the front’ model. Instead we each led a station and created a circus of activities for the students to rotate around in groups of 7 or 8. At my station I had 3 fluorescent tubes – the very kind of lightbulb they were familiar with from their classrooms. After thinking about how these lightbulbs work and why they are different to other types of bulbs, I challenged them to light it using nothing but their bare hands. The beady eyed spotted a plasma ball that I’d placed on one side and all of them joined in, speculating how it could be of use in the challenge. It’s a fantastic trick and I find students love to watch the plasma lines connect to their fingertips. The plasma ball can be used to introduce analogies to radio antennas and mobile phone screens – things they use in their everyday lives.

It was not long before we had the chance to team up and put our ideas into action. The outreach I had done to date had all been as an individual or as a pair. Here, we were in a team of 4 and so we decided to make the most of the extra pairs of hands and move away from the ‘teacher at the front’ model. Instead we each led a station and created a circus of activities for the students to rotate around in groups of 7 or 8. At my station I had 3 fluorescent tubes – the very kind of lightbulb they were familiar with from their classrooms. After thinking about how these lightbulbs work and why they are different to other types of bulbs, I challenged them to light it using nothing but their bare hands. The beady eyed spotted a plasma ball that I’d placed on one side and all of them joined in, speculating how it could be of use in the challenge. It’s a fantastic trick and I find students love to watch the plasma lines connect to their fingertips. The plasma ball can be used to introduce analogies to radio antennas and mobile phone screens – things they use in their everyday lives.

I loved working at my station and having several small groups visit me. It gave the quieter students a chance to participate and it allowed me to learn from each group and adapt for the next. We received excellent feedback from the teachers who said the dynamic style and smaller group structure kept the students much more engaged than in a larger class. I took the same activity to a science fair in Bristol and was amazed at how easily it could be adapted for children of all ages and background.

Although school classes can provide a challenging audience for outreach activities, I hope that as outreach continues to grow in popularity, scientists will seek out opportunities to take the fun and freedom of science fair demos into the classroom, to those who have not yet had chance to experience them.